Dandelions…

…are the archetypal wildflower, irrepressible and ubiquitous as sunshine.

They grow everywhere in the world, and are instantly recognisable by their buttery yellow blossoms, delicate seedheads, and deeply serrated leaves, from which their name (from the French “dent de lion”) derives.

Native to both Europe and Asia, dandelions were brought to the New World as a medicinal herb and edible plant. Every part of the plant is useful. The greens are eaten as a nourishing salad in early Spring; the flowers can be eaten raw or as fritters; they can be infused for tea, wine or medicinal vinegar and honey. The buds can be briefly boiled and eaten like Brussels sprouts, and the roots are dried and ground as a coffee substitute.

Dandelions feature in every tradition of herbal medicine in the world, although they are used for different purposes in European, Chinese, Indian and Russian systems of traditional medicine.

The taproots yield a milk similar to that of the rubber tree, that can be used in similar ways.

They provide nectar for over 187 different species of wild bees, and are an important food source for butterflies and many other insects, as well as birds. Since they start to bloom early in the year when there are relatively few other flowers, they help the Spring pollinators survive until there are other food sources available.

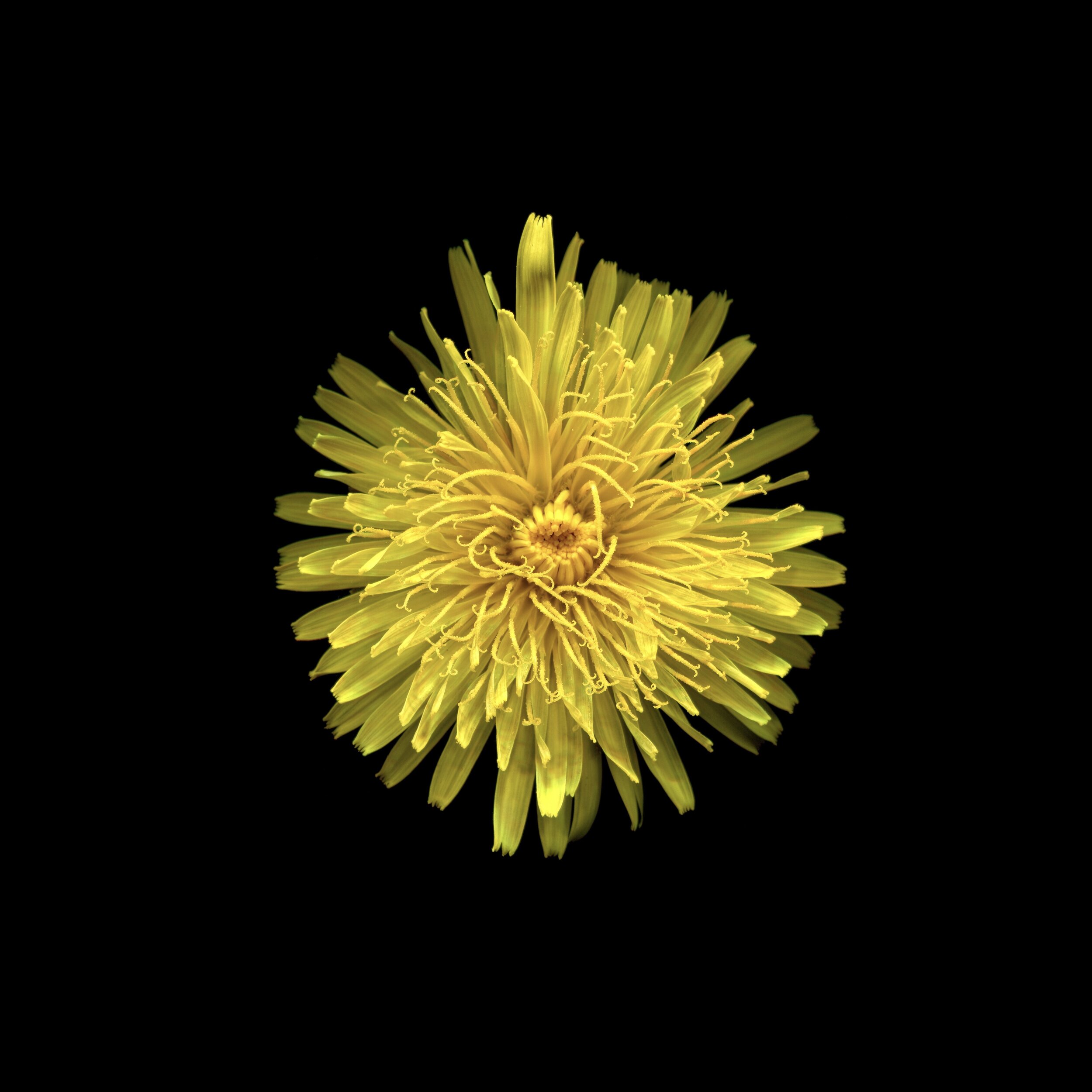

No two dandelions are exactly alike. Like snowflakes (but lending themselves more readily to sustained observation) each one is unique. I’m sure this is true of everything, of all living things, of all things of whatever nature… but it is particularly striking when each dandelion looks so similar at first glance, so immediately and unmistakably a “dandelion”, and yet with its own character.

Dandelion: no two alike

Dandelion half-clock

Wonky dandelion

Dandelion: Fly away

A stampede of dandelions

Dandelion: Disintegrating

Dandelion: leaf miner doodle

A perfect dandelion clock